📌 Responding to MISINFORMATION in our political conversations

How to Have Better Political Conversations, Part I

Welcome to How to Resist, a newsletter that shares acts of nonviolent resistance, mutual aid, and community building for ordinary folks.

I hope this inspires new ideas and helps you discover ways to engage that are right for you. If you like this content, act on it! Find something today that speaks to you and make it happen! In the words of Anthony Marra, “A single whisper can be quite a disturbance when the rest of the audience is silent.”

At this point, I’m sure we have all been in a situation in which we have heard someone make a political statement that is simply stunning in its lack of factual basis.

In these moments, we want the irrefutable; to pull out a pile of rock-solid evidence, incontrovertible facts, and undeniable visualizations so we can declare checkmate and leave our opponent with no option but to admit defeat and change their mind.

I’m curious, though, how is that working out?

What if it’s not about facts?

More likely than not, we aren’t changing anyone’s mind this way; no matter how bulletproof the evidence. Why is that? Because political beliefs are about much more than facts.

People are more likely to believe misinformation if:

It comes from in-group sources rather than out-group sources

They judge the source to be credible (not factual, but credible)

The statement appeals to emotions such as fear and outrage

The information is repeated1

Misinformation drives polarization, and the more polarized the political landscape, the more resistant people are to their misinformation being corrected by evidence.2

But there is another variable at play that makes people cling so desperately to their misinformation: ANXIETY.

Understanding the Role of Anxiety

Being confronted with information that challenges our beliefs creates anxiety. The greater the distance between the new information and the belief, the more anxiety is generated. If the anxiety becomes too great, we may well reject the new information to avoid the uncomfortable dissonance of holding two radically conflicting notions in our heads at the same time.3

This kind of personal anxiety that comes from new information challenging a closely-held belief can be exacerbated by the social anxiety created by rejecting a belief held by one’s social group, and also anxiety one has about the future, for which the misinformation is a reassuring balm.4

Oh boy, so now what?

Well, the good news is that we no longer need to drive around town practicing our fact-based comeback lines to the week’s latest disinformation. It’s likely not to work, anyway.

The bad news is that we are going to have to let go of the idea of a quick verbal K.O. Instead, we’re going to have to settle in for some real human-to-human conversation in which we explore fears, motivations, hesitations, and shared values.

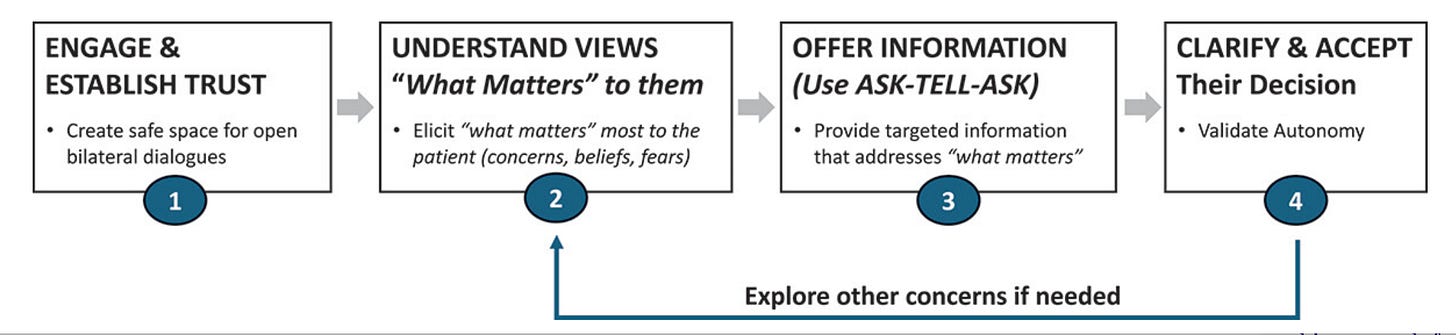

4 steps to responding to misinformation in our political conversations

Engage with the intention of creating a safe space to freely express opinions, beliefs, and knowledge gaps

Work to understand what matters most to the individual

Gently offer information to co-build accurate knowledge and guide the individual toward a new belief

Clarify and accept their decision to validate thier decision-making autonomy5

Okay… I’m going to need to see an example of this.

Alright— let’s imagine this process as a conversation between someone who believes the COVID-19 vaccine is safe and effective and someone who is skeptical about the vaccine’s safety.

Alex (Pro-Vaccine): Hey Jamie, I know there's been a lot of talk about COVID-19 vaccines lately. How do you feel about them?

Jamie (Skeptical): Honestly, I'm not sure. I've heard so many different things, and it's hard to know what to believe.

Alex: I totally get that. There's a lot of information out there, and it can be overwhelming. What are some of your main concerns?

Jamie: Well, I'm worried about the safety of the vaccines. They were developed so quickly, and I wonder if they've been tested enough.

Alex: That's a valid concern. It's important to feel confident about what we're putting into our bodies. Did you know that even though the vaccines were developed quickly, they went through rigorous testing and trials to ensure their safety?

Jamie: I heard that, but it still feels rushed. How can we be sure they're really safe?

Alex: It's great that you're thinking critically about this. The vaccines were developed quickly because scientists built on years of previous research on similar viruses. Plus, the trials involved tens of thousands of participants, and the data showed they were both safe and effective. What matters most to you when it comes to making a decision about the vaccine?

Jamie: I guess I just want to make sure I'm not putting myself at risk. I want to protect my health.

Alex: Absolutely, your health is so important. Vaccines are designed to protect us from severe illness. By getting vaccinated, you're not only protecting yourself but also helping to protect those around you, especially those who are more vulnerable. Does that make sense?

Jamie: Yeah, it does. I hadn't thought about it that way before.

Alex: It's a lot to consider, for sure. Ultimately, the decision is yours, and it's important to feel comfortable with it. If you have any more questions or concerns, I'm here to talk about them.

Jamie: Thanks, Alex. I appreciate you taking the time to explain things. I'll definitely think more about it.

Our conversations probably won’t be as straightforward as this example and are bound to be influenced by existing relationships with the folks we are talking to and a number of other apparent and not-so-apparent factors.

An excellent book that will take you much further into this topic is Tania Israel’s Beyond Your Bubble: How to Connect Across the Political Divide, Skills and Strategies for Conversations That Work (American Psychological Association, 2020)

Beyond Your Bubble covers “strategies for effective listening, managing emotions, and understanding someone else's perspective, as well as finding common ground, avoiding self-righteousness, and telling your own story,” and provides prompts, exercises, examples, and quizzes to help you have better political conversations.

If you try this method or some of the suggestions in Beyond Your Bubble, let us know how it went in the comments!

Support How to Resist

As a librarian, I am committed to keeping How to Resist free to read and publicly available.

If you believe in the power of community-driven, nonviolent resistance and find the information here valuable, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Your support will help cover the labor and costs involved in researching, writing, and producing this newsletter and enable me to continue writing in the service of democracy, both here and abroad.

You can also make a one-time donation here: ko-fi.com/howtoresist

Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., ... & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13-29.

Hodson, J., Morales, E., & Owen, J. (2025). Using Syndemic Theory as a Framework for Understanding and Addressing Polarization and Other Anti-Social Behavior on Social Media.

McBride, M. (2021, November 26). Four Psychological Mechanisms That Make Us Fall for Disinformation. CNA. https://www.cna.org/our-media/indepth/2021/11/four-psychological-mechanisms-of-disinformation

Freiling, I., Krause, N. M., Scheufele, D. A., & Brossard, D. (2023). Believing and sharing misinformation, fact-checks, and accurate information on social media: The role of anxiety during COVID-19. New Media & Society, 25(1), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211011451

Gagneur, A., Gutnick, D., Berthiaume, P., Diana, A., Rollnick, S., & Saha, P. (2024). From vaccine hesitancy to vaccine motivation: A motivational interviewing based approach to vaccine counselling. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 20(1), 2391625. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2391625Gagneur, A., Gutnick, D., Berthiaume, P., Diana, A., Rollnick, S., & Saha, P. (2024). From vaccine hesitancy to vaccine motivation: A motivational interviewing based approach to vaccine counselling. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 20(1), 2391625. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2391625

Have ya every tried to have a calm gentle conversation with a rabid MAGA?

You are missing a crucial point which makes this example problematic and unintentionally offensive. you have to really let go of trying to convince the other person. if you are still trying to convince them as this example clearly does then you will be wasting your time as the piece begins.

the way to achieve this is to understand that at least some (if not ~~all~~ most) of the information that use I to make decisions maybe misinformation or mis-informed. Or more broadly that based on the totality of ones experience if I was in their shoes I would likely make a very similar choice and to be curious about that.